Picasso’s ‘Guernica’: 10 Facts You Didn’t Know About the Famous Painting

Internationally acclaimed Spanish artist Pablo Picasso is revered for his masterpiece ‘Guernica’ – one of the most powerful and iconic paintings in history. Picasso, who rarely mixed art and politics, painted Guernica as a reaction to the 1937 bombing of the town, situated within Basque Country, Spain, by the fascist Spanish army and its German and Italian allies. At the height of the Spanish Civil War, the three-hour long aerial attack on the town by a German aircraft, at the request of Spanish Gen. Francisco Franco’s rebel Nationalist army, left one-third of the population killed or wounded.

Guernica by Picasso (Source: sartle.com)

Guernica by Picasso (Source: sartle.com)

Picasso gifted the world with Guernica just three weeks after the attack, and the enormous artwork – both literally and figuratively – highlighting the pain and horrors of war, became one of the most moving anti-war paintings in history. Though the 3.49 metre (11 feet, 5 inches) by 7.76 metre (25 feet, 6 inches) oil-on-canvas is one of Picasso’s best-known works, there are many interesting, lesser-known facts about it. Here are ten intriguing facts about Guernica:

1. Guernica was a commissioned artwork

In 1937, Picasso was living in Paris when the Spanish Republican government approached him with a commission to produce a mural that would expose the atrocities of Gen. Francisco Franco and his allies, for their pavilion in that year’s World’s Fair. The Republicans saw the event as an opportunity to condemn the actions of Franco’s Nationalist army. Several months later, on April 26, the city of Guernica was bombed by the German aircraft, and the coverage of the widespread devastation drove Picasso to begin working on the commission.

The town of Guernica after the 1937 bombing (Source: historyextra.com/Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty Images)

The town of Guernica after the 1937 bombing (Source: historyextra.com/Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty Images)

2. Picasso was moved by an article in The Times

Picasso, who had been living in France since 1904, had not been to Spain for over three years at the time of the bombing. The artist had not witnessed the atrocities of the bombing first-hand. Nevertheless, he was deeply moved by South African-British journalist George Steer’s report of the event which was published in The Times, titled ‘The Tragedy of Guernica: A Town Destroyed in Air Attack: Eye-Witness’s Account.’ Picasso never returned to Spain.

3. Women are the main characters in Guernica

A closer look at Guernica shows that the main characters in the painting are women. A woman screaming with a dead child in her arms is one of the most powerful images in the painting. Women represent life and pain, and this could be why Picasso used women figures to convey the agony in Guernica. The other women in the painting include one that can be seen trying to escape, another with her arms in the air and another holding an oil lamp, signifying hope.

The women characters in Guernica

The women characters in Guernica

4. The painting was not always in greyscale

At one point during the painting’s development, Picasso had considered adding colour to it. He had added a red teardrop falling from a crying woman’s eye and other elements using patches of coloured wallpaper, to test the effect. But these changes did not stay, and Guernica came to be one of the most recognisable monochromatic artworks in the history of art. Using unadorned shades of grey, white and blue-black, Picasso expresses the despondency of the aftermath of the bombing.

5. Guernica was criticised and later used by Nazi Germany

Guernica’s antifascist message made it a painting discussed by scholars and intellectuals all around the world. For the same reason, it also became the butt of criticism from apologisers of fascism. The official German guidebook for Paris’s International Exposition (World’s Fair) recommended against visiting Picasso’s piece. It described the painting as “a hodgepodge of body parts that any four-year-old could have painted.”

Ironically, years later in 1990, the German military misunderstood Guernica and used it in a recruitment advertisement, with the slogan, “Hostile images of the enemy are the fathers of war.”

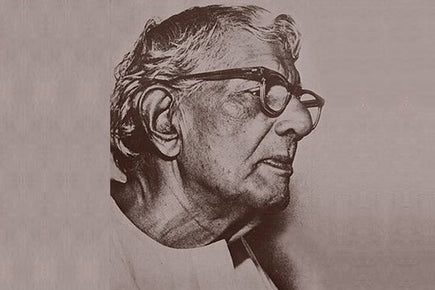

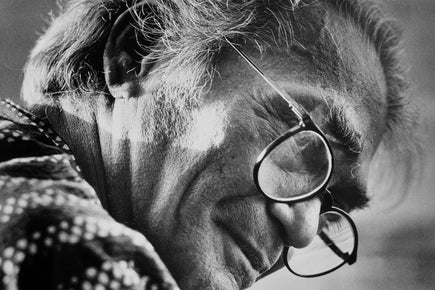

6. It inspired a biting exchange between Picasso and a Gestapo officer

Picasso’s sharp wit was almost as famous as his prodigious artistic talent. While living in Nazi-occupied Paris during World War II, a German Gestapo officer allegedly asked him, about a photograph of the painting, “Did you do that?” Picasso quick-wittedly responded, “No, you did.”

Picasso working on Guernica (Photo credit: Dora Maar/VEGAP)

Picasso working on Guernica (Photo credit: Dora Maar/VEGAP)

7. Guernica was vandalised by an anti-war activist

Picasso refused to allow Guernica to reside in Spain until liberty and democracy were established in the country. Fearing the Nazi occupation of France, he loaned the painting to the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York City in 1940. During its residency there, in 1974, anti-war activist Tony Shafrazi – who would later become one of the world’s best-known art dealers – spray-painted “KILL LIES ALL” in red paint over the painting, to make a statement against the Vietnam War. The spray paint was removed quickly, and no permanent damage was done to Guernica.

8. Picasso refused to comment on the symbolism in Guernica

The strong symbolism in Guernica – like that of the bull and the horse – has been a topic of much debate and discussion, with scholars and art experts coming up with varied interpretations. Picasso, who was naturally approached for an explanation, simply said, “This bull is a bull and this horse is a horse.” “If you give a meaning to certain things in my paintings it may be very true, but it is not my idea to give this meaning. What ideas and conclusions you have got, I obtained too, but instinctively, unconsciously. I make the painting for the painting. I paint the objects for what they are,” he added.

The bull and the horse depicted in Guernica

The bull and the horse depicted in Guernica

9. Guernica wasn’t always lauded as a masterpiece

Though Guernica is hailed as one of Picasso’s finest works, it wasn’t always met with the same enthusiasm – early reviews of the painting were especially harsh. American critic Clement Greenberg called Guernica “jerky” and “compressed.” French painter and communist Edouard Pignon criticised the painting for its supposedly misplaced political message and lack of empathy for the working class. Sharing the same sentiment, French philosopher Paul Nizan called Guernica a product of the bourgeoisie mentality.

10. A reproduction of the painting was once covered up at the UN

The entrance to the United Nations Security Council was adorned with a tapestry reproduction of Guernica from 1985 to 2009. In February 2003, then-US Secretary of State Colin Powell testified in favour of America’s declaration of war on Iraq, on site at the UN. The tapestry of Guernica remained covered with a large blue curtain during the speech, which was broadcasted. Reports stated conflicting motives for the decision – journalists thinking the violent imagery could have been unpleasant for viewers, and the George W. Bush administration deeming the famous anti-war painting as an inappropriate backdrop for a declaration of war.

Tapestry of Guernica at the UN Headquarters (Source: guernicaremakings.com/photograph by Joe Hague)

Tapestry of Guernica at the UN Headquarters (Source: guernicaremakings.com/photograph by Joe Hague)

Today, Guernica resides at the Museo Reina Sofía (Queen Sofía Museum) in Madrid, Spain. It is one of the most discussed, politically charged and relevant artworks of all time, foregrounding the sorrow and horrors of war, sans any victory. The painting, with its melancholy greys and suffering figures, urges viewers to reflect, introspect and empathise. Decades after its creation, Guernica still continues to accurately exemplify Picasso’s own resounding words: “A work of art must make a man react… It must agitate him and shake him up.”