Loading...

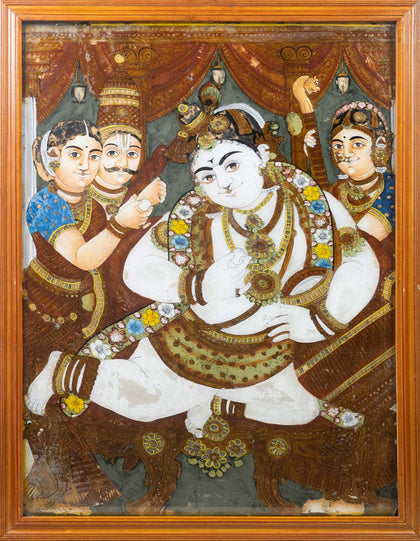

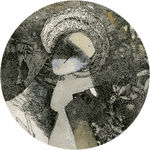

Bala Krishna - 04

Price on Inquiry

All orders are insured for transit.

This item cannot be shipped outside India.

Please enter the email address linked to your Artisera account, and we will send you a link to reset your password.

Sign Up to access your Wish List and hear from us on all that’s new!

Loading...

All orders are insured for transit.

This item cannot be shipped outside India.

All orders are insured for transit.

This item cannot be shipped outside India.

| Size: | 23 x 17 inches (framed) |

| Medium: | Reverse Glass Painting |

| Period: | 1950s/60s |

| Origin: | Thanjavur, South India |

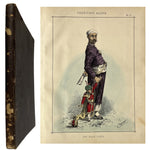

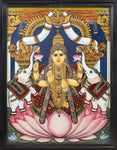

Reverse glass painting is a fascinating, yet comparatively unknown genre of Indian art. The origin of the reverse glass painting technique can be traced back to Italy, from where it spread across Europe in the 16th century. It was introduced into China by Jesuit missionaries in the 17th and early 18th century. By the second half of the 18th century, the technique was brought to India by way of the China Trade, and there flourished a brisk market for Chinese reverse glass paintings on the west coast of India. With the expansion of the British empire, the paintings found takers amongst wealthy Indian aristocrats who sought to mimic the colonial officers. And it was not long before Indian artists learnt the technique and began producing reverse glass paintings reflecting Indian tradition.

In the late 18th and early 19th century, in southern India, art was rather decadent, with a high demand for religious paintings embellished with gems, pearls and cut glass. Reverse glass paintings came as a cheap alternative, soon growing in popularity not just amongst aristocrats, but reaching a far wider audience. In the small state of Thanjavur, this distinctive school of glass painting thrived for more than a hundred years. The technique spread across western and southern India and even to former provincial Mughal capitals of Oudh and Murshidabad, as well as Rajasthan and central India, to some extent.

The term reverse glass painting describes both, how the painting is executed, and how, once completed, it is viewed. A laborious technique, it required an artist to have a good memory of the whole composition because its components were sequentially covered while he completed the work. Artists first began with placing a clear sheet of glass on their master drawing, then drew the finer lines and details. Any foil, paper or sequins, if used, were added at this stage. Then, the larger areas of opaque colour (usually tempera) were applied, and ‘shading’ was used to achieve gradation of colour. The painting was finally mounted with the unpainted side foremost.

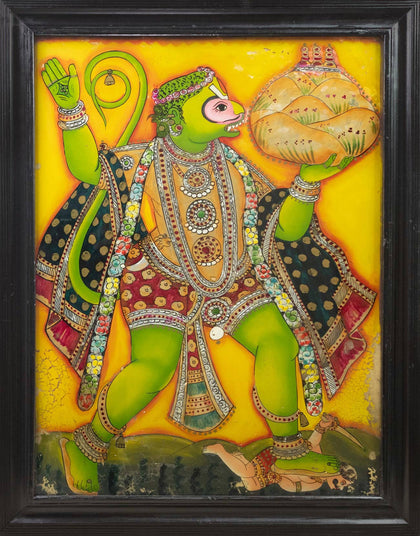

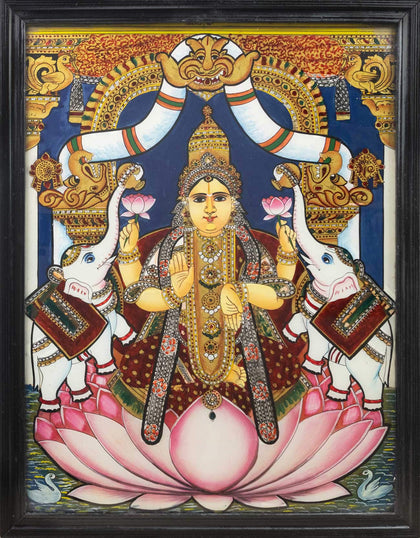

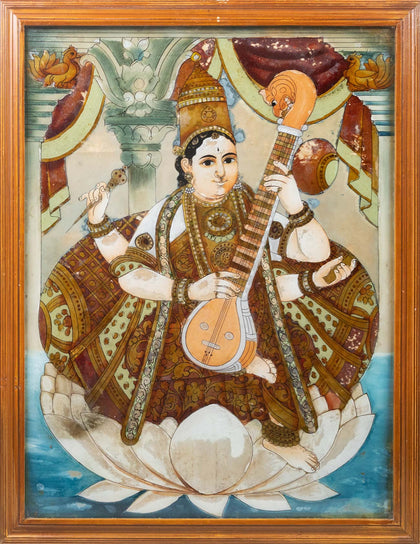

Scenes and characters from Indian mythology are recurrent in Indian reverse glass paintings, while secular themes such as portraits of kings, nobles, courtesans and musicians are also commonly depicted. The paintings are characterized by their bold style, rich colours and subjects portrayed in opulence.

Imported from Europe via China, a distinctive feature of the reverse glass technique in India was its eclectic style - a fascinating mixture of Indian and Western elements. This style reflected the aesthetics and aspirations of the time. The popularity of theatre, for instance, can be seen in the elaborate curtains that frame most paintings. Elements drawn from colonial architecture, interior decoration, and fashion also permeated the repertoire of the artists, evident in the way they portrayed deities and mythological incidents.

While reverse glass paintings flourished in India until the mid-19th century, eventually, lithographs, which were cheaper to produce and less fragile, replaced them forever.

| Size: | 23 x 17 inches (framed) |

| Medium: | Reverse Glass Painting |

| Period: | 1950s/60s |

| Origin: | Thanjavur, South India |

All orders are insured for transit.

This item cannot be shipped outside India.

This item has been added to your shopping cart.

You can continue browsing

or proceed to checkout and pay for your purchase.

This item has been added to your

shopping cart.

You can continue browsing

or proceed to checkout and pay for

your purchase.

This item has been added to your wish list.

You can continue browsing or visit your Wish List page.

Are you sure you want to delete this item from your Wish List?

Are you sure you want to delete this

item from your Wish List?

Thank you for sharing your email address!

You’ll shortly receive a Welcome Letter from us.

Please check your spam folders if you can’t

locate the email in your inbox.

Thank you for sharing your email address! You’ll shortly receive a Welcome Letter from us. Please check your spam folders if you can’t locate the email in your inbox.